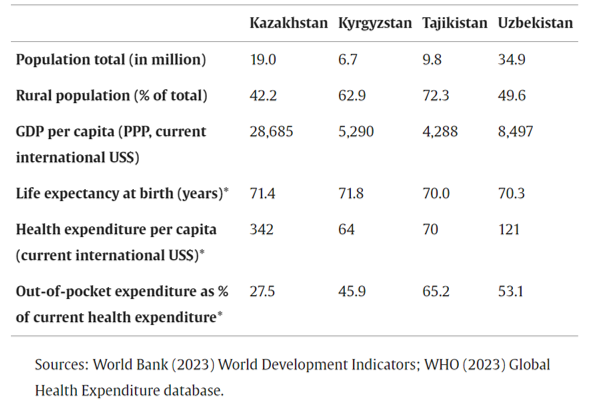

There is a shared understanding among Central Asian countries that investments in healthcare and well-being are essential to realizing the countries’ potential. However, the WHO-supported goal of providing universal healthcare coverage (UHC) requires the countries to seek a sustainable model of financing even the current healthcare spending, which remains well below WHO’s average health expenditure per capita (around USD 1,000).

Image: Countries at a glance. Source

WHO recommends the low- and lower-middle-income countries - i.e. all countries in the region except Kazakhstan - to rely on the general budget to build financially sustainable, equitable and efficient health systems. For the ever-constrained state budgets of the developing regional economies this approach has proven to be challenging.

The mandatory health insurance model, co-funded by employer and employee, introduced in Kyrgyzstan in the 1990s and Kazakhstan in 2015, became the primary instrument of sharing the financial burden with the population while pooling resources to enhance accessibility of healthcare to the citizens. Following Uzbekistan’s recent announcement of transition to compulsory medical insurance, the latest of all three countries in focus, we take a closer look at some aspects of healthcare financing reforms in the region.

System Fragmentation

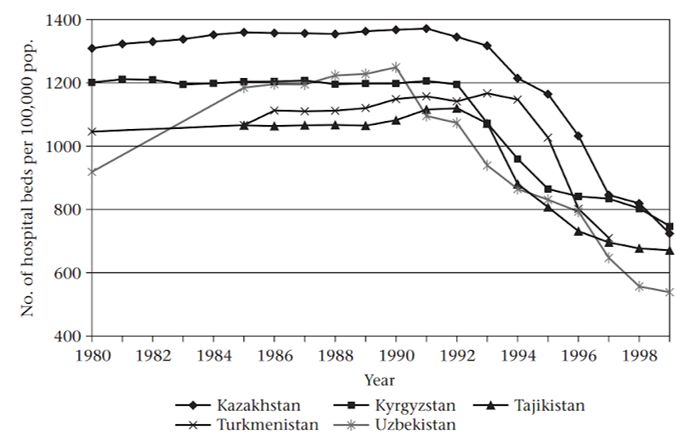

The collapse of the Soviet state-funded healthcare system resulted in the fragmentation of healthcare provision and an overall decline in the quality and availability of healthcare services. As Central Asian states cut public health funding due to tax collection freefall and struggled to keep the provision of basic health services afloat, the privatization drive of the 90s created a dual system of private and public healthcare providers. While the private sector moved into the more lucrative niches, the state - and state budgets - remained responsible for critical and costly areas of health, such as emergency and acute care, communicable and non-communicable diseases, maternal health & pediatrics, and so on.

Image: No. of hospital beds per 1000,000 pop. Source

To make ends meet, the governments gradually legalized ‘user charges’ for the patients of the state-run hospitals, who, for instance, had to pay for their own food, drugs, and medical supplies. This sector commercialization - both formal and informal - resulted in the dramatic rise of out-of-pocket (OOP) spending on health, currently accounting for between 30 and 50% of all national health expenditures.

The early (and mostly unsuccessful) regional attempts at compulsory medical insurance in the late 90s sought funds to support the budget spending on the state-owned facilities rather than bridging a widening accessibility gap between public and private health services. (“Health care systems in transition”, Judith Healy et. al., Health care in central Asia, Open University Press, 2002). In the following years, as the economy and state funding for health had somewhat improved across the region, the divide between the tax-funded public health and expanding commercial medical organizations remained a defining feature of the region’s health systems.

As the government remained focused on managing critical areas (or socially significant diseases) - from oncology and cardiology to communicable diseases and maternal health - outsourcing more mundane services to the private sector and bridging the widening gap between those with access to private health and those without became the focus of the consecutive reforms.

Primary Healthcare Reforms

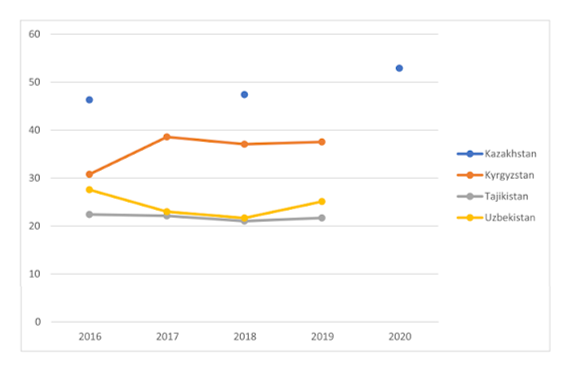

To ensure the long-term sustainability of healthcare financing and improve spending efficiency, one particular aspect to focus on in the region is the fundamental change of the primary health services. In countries with mature systems, primary healthcare professionals, such as family doctors, are the system’s foundation. Not only do they serve as the first contact for basic health needs, early diagnostics, treatment of acute conditions and chronic illnesses management, they effectively filter out and divert the flow of the patients in need of specialist care. In this role as “gatekeepers” primary health professionals protect the specialized hospitals from overflowing and patients from running into higher and unnecessary spending.

However, the primary healthcare in the region largely inherited the Soviet model (so-called Semashko model) of polyclinics where family doctors would work alongside the specialists and patients could simply go see narrow specialists in the same building. Most governments have continued to fund these polyclinics - especially in the urban centers - to provide basic health services to the population, further entrenching the model.

In Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, the state and donor funds were diverted to family doctors as a more efficient alternative to polyclinics early on. Even though primary health doctors’ official salaries in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan are now higher than those of hospital doctors, the occupation is still considered to be less prestigious and more demanding than pursuing a narrow specialist career. Shortage of family doctors and general practitioners in turn puts the pressure of providing basic health services back to polyclinics and hospitals, increasing the workload of the remaining specialists and further stretching government funds. Recent research states that even the more advanced and reformed systems face “a general underuse of primary care and an overuse of specialized and hospital care” as a result.

Image: Government expenditure of primary healthcare as a share (%) of total expenditure on primary healthcare. Source

More so, the private sector clinics popularized the polyclinic model further, as having immediate access to narrow specialists is considered to be their key advantage compared to the state sector hospitals. As people in the region tend to visit doctors when their health issues become acute and complex, they would often prefer paying extra for a specialist appointment at a private clinic to longer waiting times in the state-run system. This however further increases the patient’s financial burden, who now pays twice in the form of compulsory insurance payments and in the form of additional OOP expenses.

Inconsistent Policies

The compulsory insurance model promised to expand services beyond the guaranteed package. However, if the guaranteed packages are written into the law and are thus at least made clear to state-owned health service providers and their patients, the ‘additional’ insurance-funded package is subject to frequent changes, driven by budget availability at any given moment. The pharmaceuticals and procedures available at one point in time may become unavailable at the other. For a range of patients with chronic or acute conditions in need of consistent continuous therapy, a change of medicines or protocols could become a life and death question.

In this regard, OOP spending - i.e. being able to purchase one’s own medicines and procedures through the private sector - can be considered a balancing factor in the region’s healthcare systems. Private pharmacies and clinics cover the gaps in the public segment, be it purchases of pharmaceuticals, access to diagnostic equipment and narrow specialists, or simply relieving the burden from the overworked doctors at the polyclinics. It would have been hence logical for the state to develop policies aimed at supporting private healthcare on the one hand and reducing costs throughout the entire system on the other, since lower costs and prices in the private sector would benefit both patients and state-run insurance funds.

However, the implementation of policies aimed at cost-efficiency and cost-reduction in healthcare has to be consistent with government policies in other areas. The recent regional policy changes, such as thhe cancellation of tax incentives on medical products and services, the introduction of track-and-trace requirements for pharmaceuticals and medical consumables, preferential treatment of companies with localized production in public bids, and more stringent requirements for clinics and professionals may well be justified in its own right. These measures will almost certainly push the overall medical costs up for the state budgets, quasi-state insurance funds, and for patients alike.

Conflicting Interests: Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, where the Compulsory Social Health Insurance (CSHI or OSMS) scheme was legally adopted in 2015 and implemented from 2020, offers important learnings on the challenges to such an approach in the developing markets. Under CSHI, mandatory tax-like payments collected from companies and individual employees are pooled into the national Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF). The centralization of funds in a single operator was supposed to bring greater spending efficiency through uniformity of treatment protocols and common compensation standards. The private healthcare providers were eager to join the scheme to attract patients paid for from a single source with state guarantees.

The model however stumbled upon conflicting priorities between budget expenditure optimization and profits-driven private healthcare. As the number of patients and private providers in the system has grown, so have the costs. As the state prioritized funding access to fundamental health services through the Guaranteed Volume of Free Medical Help (or GOBMP), it limited budget transfers to SHIF to contributions for citizens exempt from compulsory medical insurance and reimbursements for selected categories of state employees. As a result, SHIF runs into continuous budget deficits and has to cut its spending on services, supplies and pharmaceuticals every year. With their bills to the fund left unpaid, clinics had to find other income streams, driving the sector commercialization further. Patients, left without access to specialists or prescribed medicines, would habitually and grudgingly pay from their pocket - or turn back to GOBMP-covered services and facilities.

The accumulated deficiencies of the system have turned SHIF’s deficit into a major crisis, requiring the intervention of the highest offices and seeking urgent solutions from the broader community of healthcare, insurance, and governance professionals. Experts cite the lack of common treatment standards and respective compensation packages, inefficiency in managing patient flows between private and public clinics, and often plain fraud, where service providers claim reimbursements for procedures that never took place as contributing factors.

Some of those issues are expected to be resolved through enhanced digitalization - another common feature of the recent healthcare reforms in the region - or the reintroduction of commercial insurance companies into the OSMS for greater standardization, transparency, and traceability.

Nonetheless, for all the potential gains in efficiency, the current regulatory trajectory inevitably leads to further raising mandatory contributions for individuals and companies, which are not dissimilar to progressive income tax and hence limited in potential scope. The bigger question is whether the compulsory insurance model with limited state coverage itself could be sustainable in addressing the underlying structural reason for increased health expenditure - the growing population demand for quality health services.

The Benefits of Healthcare Financing Reforms

Healthcare reforms are arguably among the most complex and contentious policy endeavors, requiring clear strategic vision, alignment between multiple stakeholders, and commitment to long-term change. Pooling the financial resources has always been deemed as a critical first step in the reforms in the region, and despite numerous shortcomings and critical issues, in all three countries these reforms have arguably improved the population’s access to healthcare services. Beyond the long-term results - such as increasing life expectancy and lower child mortality - the reforms have also to some extent addressed the financial protection of citizens, i.e. not exposing them to financial hardship when accessing necessary medical services.

In Kyrgyzstan, the smallest of three countries, healthcare reforms, including compulsory medical insurance, started the earliest and went the deepest with a focus on primary healthcare provision, especially in rural areas, and financial sustainability. As a result, not only has the country managed to reduce the mortality from major diseases, but it has improved the patients’ perceptions of healthcare services quality and financial protection from catastrophic spending in health emergencies. The inclusion of private providers into the compulsory insurance system envisioned in the 2024’s Health Law may further expand access to quality healthcare.

In Kazakhstan with its advanced compulsory medical insurance scheme, covering the majority of the population, and the state-funded guaranteed medical help package, OOPs share in medical expenses remains the lowest among all Central Asian nations. Even after a recent spike, the share of costs borne by patient in Kazakhstan is almost two times lower than the region’s average of 58% and is comparable to the WHO’s average for the European Region. The lively political debate on the future of OSMS is also a testament to Kazakhstan’s advanced expert community role in the decision-making process.

Uzbekistan took the primary healthcare-focused approach to massive healthcare reforms since 2018. The success of implementing new systems in the pilot project in Syrdarya Region reaffirmed the critical importance of health financing reforms and the key role of social health insurance payments through a single fund (Social Health Insurance Fund in this case) - on par with further digitalization and introduction of a unified e-health system. It is this success that precipitated the rollout of health insurance coverage in Tashkent and they beyond announced in September 2024.

In a sense, all three countries find themselves at different stages of healthcare financing reforms, and are uniquely positioned to learn from each other's successes and shortcomings. If successful, such reforms can lead to a more equitable distribution of healthcare resources, increase the efficiency of government funds, and reduce out-of-pocket expenses for citizens. More so, the inclusion of private providers of health services may complement the efforts at primary and critical care, addressing the rising expectations of a more affluent and demanding population. This dual approach—strengthening compulsory health insurance alongside fostering private sector involvement— may fall short of universal healthcare coverage in the foreseeable future, but holds the potential to alleviate some of the critical financial barriers to healthcare access in the region.

Cover photo: Social Health Protection Network (P4H)