This article is co-authored with Eldaniz Gusseinov and originally published in The Diplomat.

The historical ties between India and the Caucasus and Central Asia, connected with each other through mutual trade, religious and cultural influence, and even ruling dynasties, go back several millennia. Amid the global powers’ competition for influence in the region, today’s India is also seeking its place, and its economic and foreign policy will play an important role in the region’s development.

In particular, India’s strategic 10-year agreement with Iran for the use of the Chabahar Port, along with negotiations for a free trade agreement (FTA) with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), demonstrates the country’s determination to strengthen its economic and political presence in Eurasia.

In particular, India’s strategic 10-year agreement with Iran for the use of the Chabahar Port, along with negotiations for a free trade agreement (FTA) with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), demonstrates the country’s determination to strengthen its economic and political presence in Eurasia.

From Security to Economic Cooperation

The recent history of India-Central Asia engagements has been largely focused on security cooperation, given shared concerns around the situation in Afghanistan and spread of religious extremism in particular. The very first official delegation after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s inaugural India-Central Asia Summit in 2021 was led by the country’s national security advisor, not the minister of industry and commerce. India’s presence at two military bases in the region – Farkhor and Gissar air bases in Tajikistan – plays an important role in India’s strategic positioning in Central Asia, against the backdrop of China’s growing presence.

However, the massive disruptions to global and regional trade brought by successive crises – COVID-19, the fall of the Afghan government, the war in Ukraine, and attacks on vessels in the Red Sea – inevitably resulted in India’s rethinking of its trade routes and supply chains. The fundamental challenge to trade diversification is India’s strained relations with neighboring rivals Pakistan and China, effectively blocking the overland routes to the countries west of India’s border. The 10-year Chabahar port agreement signed with Iran in May this year would allow India to bypass maritime choke points by moving goods through Iran to the South Caucasus, Central Asia, and wider Eurasia – but where exactly would Indian trade go from there?

Among the immediate beneficiaries of India’s engagement in the Caucasus is Armenia. A small land-locked country, Armenia faces similar challenges to its trade, with neighboring Turkey and Azerbaijan sustaining a border blockade since the First Karabakh War in the early 1990s. Armenia, however, retained access to maritime trade through Georgia and Iran, and developed close diplomatic, economic, and security ties with the latter, opening a route for Indian goods. In the last two years, trade between India and Armenia has grown rapidly to $360 million, with a quarter of it accounting for the record-breaking exports of Indian weapons and military equipment, another sign of Armenia’s quest to reduce its security dependency on Russia.

The blossoming security cooperation, however, is not the only sign of deepening bilateral ties. India exports pharmaceuticals, consumer goods, machinery, and, in another unlikely twist, labor. In the last two years Armenia witnessed an unprecedented influx of Indian labor migrants to the country’s booming construction and service sectors.

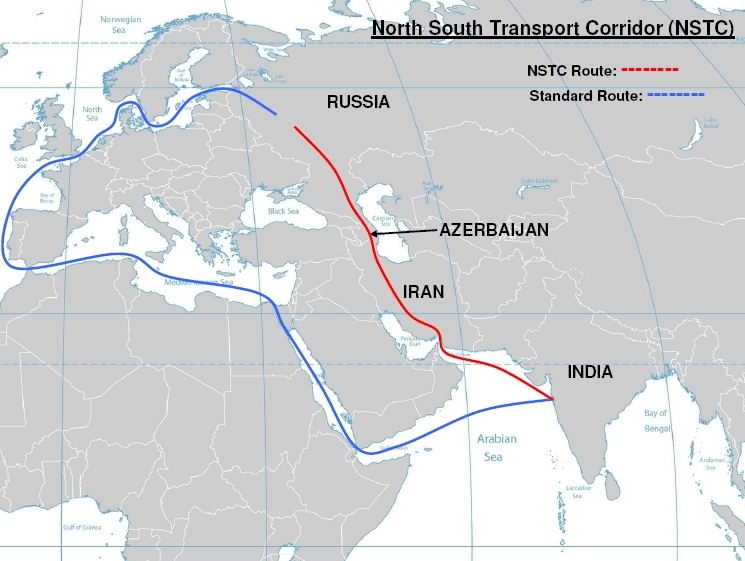

Indian engagement with Armenia, however, is paired with competing interests of other players, in particular Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan not only exports over $1.6 billion of crude oil to India, but serves as a critical juncture of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) connecting India to Russia through Iran.

INSTC, the ambitious 7,200-km long multimodal route, was conceived in the early 2000s as an alternative to the standard maritime route passing through the Suez Canal toward the Mediterranean but was significantly slowed due to sanctions on Iran, which delayed financing and construction. Although dry-runs and minor shipments did prove the route’s viability, INSTC remained largely dormant until the war in Ukraine and Russia-Iran rapprochement brought it back into focus. This year Azerbaijan completed reconstruction of the Astara terminal and with the completion of the last missing Rasht-Astara railway link expected in 2028, INSTC will become fully operational.

The initial INSTC agreement also included three Central Asian countries as signatories – Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Kazakhstan in particular remains the largest trade partner of India in the region and its major supplier of uranium. However, while India-Kazakhstan bilateral trade continues growing, it remains a fraction of Kazakhstan’s trade with China, which reached a record-high $31 billion in 2023. As Kazakhstan’s strategic focus shifted to the Middle Corridor, an increasingly attractive alternative route connecting China to Europe, INSTC’s eastern leg running through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan may require additional financial and political nudge from the project’s backers (Russia and India in particular).

The recent history of India-Central Asia engagements has been largely focused on security cooperation, given shared concerns around the situation in Afghanistan and spread of religious extremism in particular. The very first official delegation after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s inaugural India-Central Asia Summit in 2021 was led by the country’s national security advisor, not the minister of industry and commerce. India’s presence at two military bases in the region – Farkhor and Gissar air bases in Tajikistan – plays an important role in India’s strategic positioning in Central Asia, against the backdrop of China’s growing presence.

However, the massive disruptions to global and regional trade brought by successive crises – COVID-19, the fall of the Afghan government, the war in Ukraine, and attacks on vessels in the Red Sea – inevitably resulted in India’s rethinking of its trade routes and supply chains. The fundamental challenge to trade diversification is India’s strained relations with neighboring rivals Pakistan and China, effectively blocking the overland routes to the countries west of India’s border. The 10-year Chabahar port agreement signed with Iran in May this year would allow India to bypass maritime choke points by moving goods through Iran to the South Caucasus, Central Asia, and wider Eurasia – but where exactly would Indian trade go from there?

Among the immediate beneficiaries of India’s engagement in the Caucasus is Armenia. A small land-locked country, Armenia faces similar challenges to its trade, with neighboring Turkey and Azerbaijan sustaining a border blockade since the First Karabakh War in the early 1990s. Armenia, however, retained access to maritime trade through Georgia and Iran, and developed close diplomatic, economic, and security ties with the latter, opening a route for Indian goods. In the last two years, trade between India and Armenia has grown rapidly to $360 million, with a quarter of it accounting for the record-breaking exports of Indian weapons and military equipment, another sign of Armenia’s quest to reduce its security dependency on Russia.

The blossoming security cooperation, however, is not the only sign of deepening bilateral ties. India exports pharmaceuticals, consumer goods, machinery, and, in another unlikely twist, labor. In the last two years Armenia witnessed an unprecedented influx of Indian labor migrants to the country’s booming construction and service sectors.

Indian engagement with Armenia, however, is paired with competing interests of other players, in particular Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan not only exports over $1.6 billion of crude oil to India, but serves as a critical juncture of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) connecting India to Russia through Iran.

INSTC, the ambitious 7,200-km long multimodal route, was conceived in the early 2000s as an alternative to the standard maritime route passing through the Suez Canal toward the Mediterranean but was significantly slowed due to sanctions on Iran, which delayed financing and construction. Although dry-runs and minor shipments did prove the route’s viability, INSTC remained largely dormant until the war in Ukraine and Russia-Iran rapprochement brought it back into focus. This year Azerbaijan completed reconstruction of the Astara terminal and with the completion of the last missing Rasht-Astara railway link expected in 2028, INSTC will become fully operational.

The initial INSTC agreement also included three Central Asian countries as signatories – Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Kazakhstan in particular remains the largest trade partner of India in the region and its major supplier of uranium. However, while India-Kazakhstan bilateral trade continues growing, it remains a fraction of Kazakhstan’s trade with China, which reached a record-high $31 billion in 2023. As Kazakhstan’s strategic focus shifted to the Middle Corridor, an increasingly attractive alternative route connecting China to Europe, INSTC’s eastern leg running through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan may require additional financial and political nudge from the project’s backers (Russia and India in particular).

India as a Balancing Force

Similar geopolitical dynamics will shape India’s relations with other countries in Central Asia. Lacking China’s construction overcapacity, for the foreseeable future India will be unable to offer massive infrastructure development projects comparable to the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to the region, where connectivity remains a critical issue. Neither does India, focused on ramping up domestic infrastructure, play an active role in the investment-heavy projects in Central Asia’s energy sector and other critical industries where companies from the Gulf countries and China are taking a lead. Despite some early success of taking part in infrastructure projects in Central Asia throughout the 2000s, India’s existing $1 billion credit line for infrastructure development in Central Asia remains unutilized.

However, while India’s economic leverage in the region will likely remain limited, it can nonetheless act as a balancing force, offsetting some of the region’s security concerns through diplomatic and limited military cooperation. One example of such an approach is a regular joint military exercises with Uzbekistan. Though small-scale, the exercises have now run regularly for five years in a row (with a COVID-related hiatus), while joint anti-terror drills with China took place only once, in 2019.

Another important factor is that pursuing the role of leader of the so-called Global South, India managed to attract Central Asian leaders to join its Voices of Global South Summit, a new platform for diplomatic cooperation, and may further use its weight on the international arena for the benefit of the region’s smaller countries.

In the meantime, existing areas of economic cooperation in vital sectors may further strengthen and expand India’s presence in Central Asia. Beyond trade in raw materials and hydrocarbons, INSTC development or its interlinking with the Middle Corridor’s railways infrastructure (Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, or TITR) may boost trade in agriculture and textiles, long ago identified as areas of interest for the Indian business community. More so, cooperation in other sectors, such as healthcare and digital technology, may develop independently of INSTC progress.

For instance, there is a shared understanding that India-Central Asia cooperation in medical education, research, manufacturing, and even medical tourism is of strategic importance for bilateral ties. Indian pharmaceuticals lead the country’s exports to the Caucasus and Central Asia. Indian healthcare giants may further benefit from exploring the emerging medical production clusters, such as Tashkent Pharma Park or Kazakhstan initiative to develop pharmaceutical transportation hubs, to grow their market share and strengthen positions in the region.

India’s world-class experience in IT, another sector identified by mutual agreements as an area for fruitful cooperation, remains surprisingly underutilized. While Central Asian countries, such as Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, model their IT sector development after India’s rapid growth as a software outsourcing giant, there is seemingly little cooperation between Indian and Central Asian IT companies to date. In part, this could be explained by considerations that the developing outsourcing hubs in Central Asia will naturally compete with India’s role in the sector, as well as by India’s own VC market woes. Nonetheless, deeper ties may uncover new models of joint IT development, open up new markets on the continent and beyond, and bring much needed capital and expertise to the region.

Similar geopolitical dynamics will shape India’s relations with other countries in Central Asia. Lacking China’s construction overcapacity, for the foreseeable future India will be unable to offer massive infrastructure development projects comparable to the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to the region, where connectivity remains a critical issue. Neither does India, focused on ramping up domestic infrastructure, play an active role in the investment-heavy projects in Central Asia’s energy sector and other critical industries where companies from the Gulf countries and China are taking a lead. Despite some early success of taking part in infrastructure projects in Central Asia throughout the 2000s, India’s existing $1 billion credit line for infrastructure development in Central Asia remains unutilized.

However, while India’s economic leverage in the region will likely remain limited, it can nonetheless act as a balancing force, offsetting some of the region’s security concerns through diplomatic and limited military cooperation. One example of such an approach is a regular joint military exercises with Uzbekistan. Though small-scale, the exercises have now run regularly for five years in a row (with a COVID-related hiatus), while joint anti-terror drills with China took place only once, in 2019.

Another important factor is that pursuing the role of leader of the so-called Global South, India managed to attract Central Asian leaders to join its Voices of Global South Summit, a new platform for diplomatic cooperation, and may further use its weight on the international arena for the benefit of the region’s smaller countries.

In the meantime, existing areas of economic cooperation in vital sectors may further strengthen and expand India’s presence in Central Asia. Beyond trade in raw materials and hydrocarbons, INSTC development or its interlinking with the Middle Corridor’s railways infrastructure (Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, or TITR) may boost trade in agriculture and textiles, long ago identified as areas of interest for the Indian business community. More so, cooperation in other sectors, such as healthcare and digital technology, may develop independently of INSTC progress.

For instance, there is a shared understanding that India-Central Asia cooperation in medical education, research, manufacturing, and even medical tourism is of strategic importance for bilateral ties. Indian pharmaceuticals lead the country’s exports to the Caucasus and Central Asia. Indian healthcare giants may further benefit from exploring the emerging medical production clusters, such as Tashkent Pharma Park or Kazakhstan initiative to develop pharmaceutical transportation hubs, to grow their market share and strengthen positions in the region.

India’s world-class experience in IT, another sector identified by mutual agreements as an area for fruitful cooperation, remains surprisingly underutilized. While Central Asian countries, such as Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, model their IT sector development after India’s rapid growth as a software outsourcing giant, there is seemingly little cooperation between Indian and Central Asian IT companies to date. In part, this could be explained by considerations that the developing outsourcing hubs in Central Asia will naturally compete with India’s role in the sector, as well as by India’s own VC market woes. Nonetheless, deeper ties may uncover new models of joint IT development, open up new markets on the continent and beyond, and bring much needed capital and expertise to the region.

Indo-Iranian Interplay in the Indian Intentions in Central Asia

The temporary free trade agreement (FTA) between Iran and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which came into effect in 2019, had significant impacts on economic relations between Iran and EAEU member states, particularly Kazakhstan. The interim FTA led to a substantial increase in trade between Kazakhstan and Iran. By the end of 2022, the trade turnover between the two countries reached $521.4 million, an 18.3 percent increase compared to the previous year. Exports from Kazakhstan to Iran accounted for $309.7 million, reflecting a 12.5 percent rise, while imports from Iran to Kazakhstan reached $211.7 million. Kazakhstan leveraged the FTA to enhance exports of agricultural products, particularly grain, to Iran. The new agreement between Iran and the EAEU guaranteed duty-free supplies of Kazakh grain within specified tariff quotas, facilitating smoother trade in agricultural goods.

One of Kazakhstan’s main priorities in the EAEU is to expand the organization’s international ties in order to further promote a multi-vector foreign policy. With Kazakhstan’s accession to the EAEU, a number of restrictions were automatically imposed on other external actors in the development of trade relations with the country, which put Russia in a more favorable economic position. And at this stage, Russia’s economic presence in Kazakhstan is growing, and both for Kazakhstan and other EAEU members, such as Kyrgyzstan, India’s membership in the free trade zone is strategically important. The expansion of EAEU membership may also increase the popularity of the organization among other Central Asian countries, in particular Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, as it will no longer be an organization with a single large player, but have a more dynamic and flexible structure.

India’s inclusion in the EAEU would further strengthen its geopolitical ties with Central Asian countries, aligning with India’s “Connect Central Asia” policy aimed at deepening economic, cultural, and security cooperation. Expert evaluations suggest that the GDPs of current EAEU member states would increase significantly with India’s inclusion, and India’s GDP could register a 3 percentage point increase, underscoring the economic benefits of the agreement. Given India’s strong relations with Iran, INSTC in this regard comes as a natural connection and addresses economic interests of both countries.

These economic considerations, however, may come secondary to India’s strategic interests in securing its future access to energy sources, critical materials, and international markets required to sustain the country’s growth. From this perspective, the fate of INSTC, EAEU, and other ambitious projects – such as the revival of the long-delayed project of Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline (TAPI) – will continue to depend on the complex interplay of international sanctions on Iran and Russia, the security situation in Afghanistan and its uneasy relations with its neighbors, economic and political interests of global powers and regional players, and, most importantly, India’s own vision of its role in the region and beyond.

Conclusion: India’s Strategic Push in Central Asia and South Caucasus

In the environment of geopolitical competition in the region, it is clear that India’s rich history of smart diplomatic maneuvering will continue to be tested in the Caucasus and Central Asia. By securing the Chabahar port agreement with Iran and negotiating a free trade agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union, India is positioning itself to build viable alternatives to the traditional trade routes and expand its economic influence.

The shift from a security-focused engagement to broader cooperation with the Caucasus and Central Asian states underscores India’s pursuit of strategic depth. This transition is marked by growing trade, security ties, and even labor migration, demonstrating India’s adaptive and resilient foreign policy. As India continues to chart its foreign policy course, its economic leverage, though limited compared to China’s, will serve as a balancing force in the nations’ foreign policy. Joint military exercises, diplomatic initiatives, and participation in multilateral platforms like the Voices of Global South Summit illustrate India’s role as a stabilizing power in the region.

Future cooperation in IT, healthcare, and infrastructure development, along with ambitious projects like INSTC and TAPI, will further shape India’s role in Central Asia. Despite the challenges, India’s strategic vision and proactive diplomacy are poised to foster deeper economic and cultural ties, solidifying its status as a growing key regional player. The rise of the new global superpower may well be a welcome development for the entire region’s economy and foreign policy.

The temporary free trade agreement (FTA) between Iran and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which came into effect in 2019, had significant impacts on economic relations between Iran and EAEU member states, particularly Kazakhstan. The interim FTA led to a substantial increase in trade between Kazakhstan and Iran. By the end of 2022, the trade turnover between the two countries reached $521.4 million, an 18.3 percent increase compared to the previous year. Exports from Kazakhstan to Iran accounted for $309.7 million, reflecting a 12.5 percent rise, while imports from Iran to Kazakhstan reached $211.7 million. Kazakhstan leveraged the FTA to enhance exports of agricultural products, particularly grain, to Iran. The new agreement between Iran and the EAEU guaranteed duty-free supplies of Kazakh grain within specified tariff quotas, facilitating smoother trade in agricultural goods.

One of Kazakhstan’s main priorities in the EAEU is to expand the organization’s international ties in order to further promote a multi-vector foreign policy. With Kazakhstan’s accession to the EAEU, a number of restrictions were automatically imposed on other external actors in the development of trade relations with the country, which put Russia in a more favorable economic position. And at this stage, Russia’s economic presence in Kazakhstan is growing, and both for Kazakhstan and other EAEU members, such as Kyrgyzstan, India’s membership in the free trade zone is strategically important. The expansion of EAEU membership may also increase the popularity of the organization among other Central Asian countries, in particular Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, as it will no longer be an organization with a single large player, but have a more dynamic and flexible structure.

India’s inclusion in the EAEU would further strengthen its geopolitical ties with Central Asian countries, aligning with India’s “Connect Central Asia” policy aimed at deepening economic, cultural, and security cooperation. Expert evaluations suggest that the GDPs of current EAEU member states would increase significantly with India’s inclusion, and India’s GDP could register a 3 percentage point increase, underscoring the economic benefits of the agreement. Given India’s strong relations with Iran, INSTC in this regard comes as a natural connection and addresses economic interests of both countries.

These economic considerations, however, may come secondary to India’s strategic interests in securing its future access to energy sources, critical materials, and international markets required to sustain the country’s growth. From this perspective, the fate of INSTC, EAEU, and other ambitious projects – such as the revival of the long-delayed project of Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline (TAPI) – will continue to depend on the complex interplay of international sanctions on Iran and Russia, the security situation in Afghanistan and its uneasy relations with its neighbors, economic and political interests of global powers and regional players, and, most importantly, India’s own vision of its role in the region and beyond.

Conclusion: India’s Strategic Push in Central Asia and South Caucasus

In the environment of geopolitical competition in the region, it is clear that India’s rich history of smart diplomatic maneuvering will continue to be tested in the Caucasus and Central Asia. By securing the Chabahar port agreement with Iran and negotiating a free trade agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union, India is positioning itself to build viable alternatives to the traditional trade routes and expand its economic influence.

The shift from a security-focused engagement to broader cooperation with the Caucasus and Central Asian states underscores India’s pursuit of strategic depth. This transition is marked by growing trade, security ties, and even labor migration, demonstrating India’s adaptive and resilient foreign policy. As India continues to chart its foreign policy course, its economic leverage, though limited compared to China’s, will serve as a balancing force in the nations’ foreign policy. Joint military exercises, diplomatic initiatives, and participation in multilateral platforms like the Voices of Global South Summit illustrate India’s role as a stabilizing power in the region.

Future cooperation in IT, healthcare, and infrastructure development, along with ambitious projects like INSTC and TAPI, will further shape India’s role in Central Asia. Despite the challenges, India’s strategic vision and proactive diplomacy are poised to foster deeper economic and cultural ties, solidifying its status as a growing key regional player. The rise of the new global superpower may well be a welcome development for the entire region’s economy and foreign policy.