2024 became a watershed year for the region’s AI ambitions. With national AI strategies unveiled, local languages LLMs announced, and AI chatbots becoming part of e-gov portals, the sector developments gain pace. We explore Central Asia and Caucasus (CCA) AI ambitions, opportunities, and limitations through the three different frameworks - AI Readiness, Responsible AI, and AI Sprinters.

AI Readiness

Oxford Insight’s AI Readiness Index, measured along four pillars - government, technology, data and infrastructure, and global governance, puts CCA countries in the lower-middle category. With a maximum score of 84 points belonging to the US, CCA’s average is only 41 and even the regions’ highest scorers (48 points to Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan) are falling behind the neighboring Turkey (60 points) and Russia (62 points).

The Pillars of The AI Government Readiness Index, Oxford Insights

The Index highlights that scores in the Data and Infrastructure pillar show a substantial difference between high and low-income economies. In the Central Asia and Caucasus (CCA) region, overcoming this infrastructural bottleneck will require fundamental changes to entrenched domestic policies that have traditionally prioritized local processing over cloud solutions.

The growing demand for processing power and the scalability of AI solutions greatly exceed domestic data processing capacities. The almost inevitable transition to cloud computing must take into account that, with rare exceptions (Armenia and Georgia), the largest broadband internet providers and data centers in the region are state-owned and often quasi-monopolistic companies with vested interests in controlling data flows. Combined with the traditionally greater government interference in internet traffic due to security concerns, this explains the resistance to withdrawing mandatory data or processing localization clauses in the local legislations of Central Asia’s largest digital economies, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

In addition to physical infrastructure, connectivity, and processing limitations, Central and South Asia are also ranked as the third lowest region in terms of Data availability. In particular, the lack of high-quality datasets in local languages required to train Large Language Models (LLMs) may create hurdles to developing domestic solutions. While initiatives aimed at collating machine-readable datasets in local languages are underway (for instance in Kazakhstan), absent previous local-language content production and digitization efforts data scarcity will continue to be a major roadblock for models training.

The proposal to build a common Turkic-language LLM brought by the Organization of Turkic States earlier this year may help to overcome some of those limitations but would require a far greater level of technological cooperation between the countries than ever before. Another approach, seemingly taken by the Armenian tech sector, would be to integrate national R&D capabilities, both public and private, into the global AI race by promoting cutting-edge research and incentivizing partnerships with the leading players in the field.

In both scenarios, the maturity of each country’s tech sector will be a critical factor. AI development will put to the test the effectiveness of all the different government support models (or lack thereof) aimed at developing the local tech ecosystems and integrating them into global digital supply chains.

Responsible AI

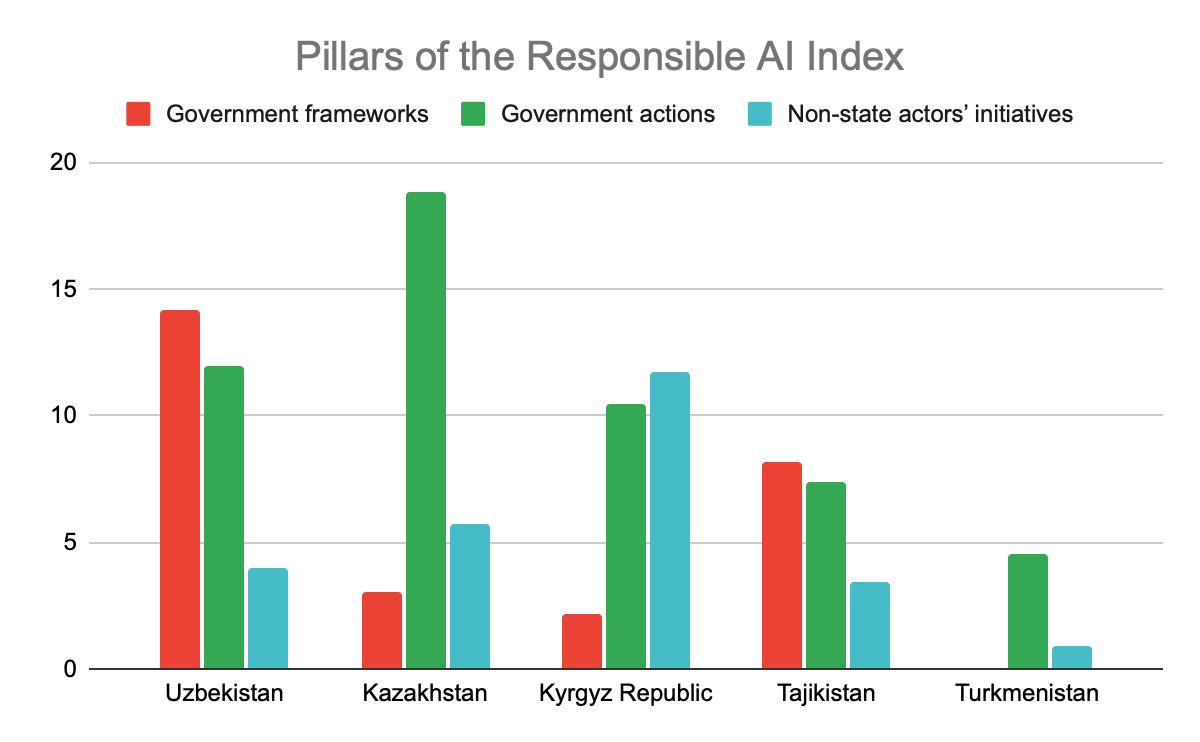

The recent Global Index on Responsible AI puts Uzbekistan ahead of all other countries in Central Asia as well as Azerbaijan and Armenia in the Caucasus. The index methodology is rather complex with 19 areas measured along three pillars of government frameworks, government actions, and non-state actors. Uzbekistan, in particular, may have the ‘first-mover’ advantage in the area of regulation, being the first country in Central Asia to introduce a separate regulatory framework on AI development back in 2021.

Conceptualizing AI development from a regulatory perspective, however, is not enough. Tajikistan had its own AI Development Strategy since 2021 but evidence of its progress is notably hard to find in the study. Kazakhstan, on the contrary, introduced its own foundational AI Development Concept for 2024-2029 just this year, but scored the highest on government actions to support AI development, and in Kyrgyzstan AI adoption is primarily driven by the non-state actors.

Conceptualizing AI development from a regulatory perspective, however, is not enough. Tajikistan had its own AI Development Strategy since 2021 but evidence of its progress is notably hard to find in the study. Kazakhstan, on the contrary, introduced its own foundational AI Development Concept for 2024-2029 just this year, but scored the highest on government actions to support AI development, and in Kyrgyzstan AI adoption is primarily driven by the non-state actors.

Responsible AI Index, Central Asia. Institute for Development of Freedom of Information

While this cursory analysis of AI adoption progress may indicate some notable differences between the countries, more importantly, both the average CCA score and countries' individual rankings are falling well behind developing Asia. To reach the level of Malaysia, the lowest country in Asia’s top ten (28 points), or the Middle East’s average of 21 points, countries in Central Asia and the Caucasus would have to improve their ranking by at least a factor of 2. Even exceptional progress in one pillar - say more government funding for AI projects - or along other indices, such as greater transparency and explainability of AI outcomes, may simply not suffice.

AI Sprinters

Google’s recent report on AI Sprinters - emerging markets with the greatest potential to reap economic and social benefits from AI transformation - puts forward four “game changers” for the four fundamental pillars of Infrastructure, People, Innovation, and Policies. These recommendations include 100% Adoption of Cloud-First Policies, National AI Skills Initiatives, Modernizing National Data Systems for the AI Era, and Promoting Innovation Through Enabling Regulation.

The Digital Sprinters Framework, Google

While some progress has been evident along those four dimensions, none of the CCA countries have implemented all four recommendations so far. For instance, only Armenia has announced Cloud First to be its foundational policy starting this year, and Special Regulatory Regimes for AI development are envisioned by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan - the two countries spending the most on aiding local tech companies and expanding IT exports.

The successful expansion of e-government in the region in the last decade provided an impetus for the development of the National Data Systems. The progress however has been uneven with Kazakhstan taking the lead in the E-Government Development Index well ahead of all other countries. Notwithstanding the improvements in infrastructure and service availability, in all countries, the traditional approach of every government agency ‘siloing’ its own data prevails. Consequently, it is unclear whether state systems and infrastructure could be considered ‘AI-ready’, or whether AI solutions could be deployed with the appropriate safety, integrity, and privacy safeguards.

Where the countries seem to agree the most is that AI Skills are critical for national development. All eight countries seek various ways to introduce AI training from schools to workplaces through partnerships with private sector players, international organizations, and education providers. While public-private partnerships in education may help to develop AI skills and knowledge in selected segments (say train more data analysts for the booming fintech industry), broader implementation of AI across all sectors, as envisioned by the AI Sprinters approach, may require developing innovative models of applying AI to enhance productivity. Having online AI classes at school will hardly be a substitute for creating continuous education opportunities for people of all ages and professional occupations and bringing more youth to take STEM specialties.

Conclusion

Central Asia and Caucasus countries are at a critical juncture of their AI journey. While the region overall and some states, in particular, have made strides in areas like regulatory frameworks, digitalization of critical services, and even AI skills development, they now face both ‘hard’ bottlenecks, such as infrastructure, connectivity, and data availability, and ‘soft barriers’, including lack of harmonized data transfer frameworks and enabling regulations. While intra-regional integration initiatives hold some promise for boosting joint AI efforts, truly unlocking its promise will require a society-wide effort to incentivize cooperation, innovation, and experimentation. The success of these efforts will determine the region's ability to leverage AI for economic and social transformation in the coming years.