Critical Raw Materials and the European Union

The world has found itself in a new era of non-renewable dependence, one potentially greater than oil or any other fossil fuel, more economically significant than gold, and more sought after than diamonds. Critical Raw Materials (CRMs) are foundational to the green energy transition with their use in solar panels, wind turbines, and Electric Vehicles (EVs), paramount to technological advancement of microchipsand batteries, and fundamental to an array of industries, from FinTech to healthcare.

The European Union (EU) defines CRMs as raw materials that are both economically significant to the EU and have a high risk of supply disruption. Since 2011, the EU has created and regularly updated its lists of CRMs, with the latest fourth list passed in 2020. The most recent official list is established by the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), adopted as Regulation (EU) 2024/1252, which entered into force on May 23, 2024. The CRMA sets targets for domestic production, processing, and recycling and introduces measures to enhance supply chain resilience.

Specifically, the EU highlights the following materials as CRMs:

The European Union (EU) defines CRMs as raw materials that are both economically significant to the EU and have a high risk of supply disruption. Since 2011, the EU has created and regularly updated its lists of CRMs, with the latest fourth list passed in 2020. The most recent official list is established by the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), adopted as Regulation (EU) 2024/1252, which entered into force on May 23, 2024. The CRMA sets targets for domestic production, processing, and recycling and introduces measures to enhance supply chain resilience.

Specifically, the EU highlights the following materials as CRMs:

Copper and Nickel are not classified as CRMs, but are included in a Strategic Raw Materials under the CRMA due to their importance for specific technologies and sectors.

Currently, less than 10% of the EU’s annual CRM consumption is sourced within the Union. The CRMA sets a binding target for domestic extraction of at least 10% by 2030. Therefore, the EU depends, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future, on the import of CRMs from outside its borders. With rising international geopolitical tensions and market shocks, such as the Chinese CRMs export restrictions, the EU seeks to diversify its suppliers. Hence, Central Asia, with its mineral wealth, political and border stability, and growing economic importance, emerges as a prime candidate for EU partnership.

Currently, less than 10% of the EU’s annual CRM consumption is sourced within the Union. The CRMA sets a binding target for domestic extraction of at least 10% by 2030. Therefore, the EU depends, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future, on the import of CRMs from outside its borders. With rising international geopolitical tensions and market shocks, such as the Chinese CRMs export restrictions, the EU seeks to diversify its suppliers. Hence, Central Asia, with its mineral wealth, political and border stability, and growing economic importance, emerges as a prime candidate for EU partnership.

EU and Central Asia

Figure 1: Countries accounting for the largest share of the global supply of CRMs. Source: European Commission Report on the 2020 criticality assessment

Since the CRMs’ boom, the EU and Central Asia made mutual efforts to expand cooperation. This includes the adoption of the 2019 EU Strategy on Central Asia, the 2023 Joint Roadmap for Deepening Ties between the EU and Central Asia, and, most notably, its first EU-Central Asia summit in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. However, the facts on the ground tell a far more nuanced story of evolving but yet limited cooperation.

Within the wider Eurasian context, the EU currently recognizes Kazakhstan as its main Central Asian partner for CRMs, with Türkiye also identified as a major supplier of specific CRMs. Additionally, companies from Kazakhstan (National Mining Company Tau-Ken Samruk JSC and Phoenix Mining LLP) participate in the European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA), which brings together a growing number of public and private organizations across the entire raw materials value chain. This limited representation of other Central Asian countries exemplifies a limited extent to which the EU has recognized the CRMs trade potential with the region.

Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, both rich in CRMs, are not yet as central to EU supply chains as Kazakhstan, though Uzbekistan is increasingly acknowledged as a strategic partner, highlighted by the 2024 EU-Uzbekistan Strategic Partnership Agreement and ongoing investments in raw material projects. Recent developments signal a deeper commitment to integrating value chains and supporting investment projects in the region, a broader and more systematic engagement with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan remains essential to fully secure and diversify the EU’s supply of CRMs.

Within the wider Eurasian context, the EU currently recognizes Kazakhstan as its main Central Asian partner for CRMs, with Türkiye also identified as a major supplier of specific CRMs. Additionally, companies from Kazakhstan (National Mining Company Tau-Ken Samruk JSC and Phoenix Mining LLP) participate in the European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA), which brings together a growing number of public and private organizations across the entire raw materials value chain. This limited representation of other Central Asian countries exemplifies a limited extent to which the EU has recognized the CRMs trade potential with the region.

Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, both rich in CRMs, are not yet as central to EU supply chains as Kazakhstan, though Uzbekistan is increasingly acknowledged as a strategic partner, highlighted by the 2024 EU-Uzbekistan Strategic Partnership Agreement and ongoing investments in raw material projects. Recent developments signal a deeper commitment to integrating value chains and supporting investment projects in the region, a broader and more systematic engagement with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan remains essential to fully secure and diversify the EU’s supply of CRMs.

Kazakhstan

Figure 2: Rare Earth Minerals’ deposits in Kazakhstan. Source: The Astana Times

Kazakhstan is the central partner of the EU in the region for the supply of CRMs. Kazakhstan currently produces or processes at least 15 out of 32 CRMs, and is ready to supply up to 21 CRMs, covering most of the CRMs on the EU’s list.

Beyond its vast CRMs reserves and production capabilities, Kazakhstan and the EU have an established and multi-layered partnership. Specifically, Kazakhstan and the EU have concluded a Memorandum of Understanding on Sustainable Raw Materials, Batteries, and Renewable Hydrogen Value Chains, an Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA), and two development Roadmaps for both the years 2023-2024 and 2025-2026.

Kazakhstan is thus the only fully recognized EU partner in Central Asia with both the resource base and the necessary legal and regulatory backing to underpin large-scale, long-term CRMs collaboration. Both sides have demonstrated a proactive, results-driven approach, evidenced by multi-million-euro investment projects, joint ventures, and a rapid expansion of trade and investment. This partnership is not only fundamental to the EU’s strategy for securing resilient and sustainable supply chains but also offers significant economic benefits for Kazakhstan, reinforcing its role as a regional leader.

However Kazakhstan faces significant limitations in infrastructure and technological capabilities. The country’s mining sector still relies on outdated equipment and lacks modern geochemistry and trade laboratory facilities, which can hinder the efficiency and quality of resource extraction and processing. Moreover, as Kazakhstan continues to exploit its natural resources, particularly through water-intensive mining operations, it risks exacerbating the regional water insecurity, potentially leading to operational delays and even shutdowns. These challenges underscore the need for the EU to go beyond the extraction operation, but offer its engineering and environmental expertise and pursue a systemic approach to its partnership with Kazakhstan.

Beyond its vast CRMs reserves and production capabilities, Kazakhstan and the EU have an established and multi-layered partnership. Specifically, Kazakhstan and the EU have concluded a Memorandum of Understanding on Sustainable Raw Materials, Batteries, and Renewable Hydrogen Value Chains, an Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA), and two development Roadmaps for both the years 2023-2024 and 2025-2026.

Kazakhstan is thus the only fully recognized EU partner in Central Asia with both the resource base and the necessary legal and regulatory backing to underpin large-scale, long-term CRMs collaboration. Both sides have demonstrated a proactive, results-driven approach, evidenced by multi-million-euro investment projects, joint ventures, and a rapid expansion of trade and investment. This partnership is not only fundamental to the EU’s strategy for securing resilient and sustainable supply chains but also offers significant economic benefits for Kazakhstan, reinforcing its role as a regional leader.

However Kazakhstan faces significant limitations in infrastructure and technological capabilities. The country’s mining sector still relies on outdated equipment and lacks modern geochemistry and trade laboratory facilities, which can hinder the efficiency and quality of resource extraction and processing. Moreover, as Kazakhstan continues to exploit its natural resources, particularly through water-intensive mining operations, it risks exacerbating the regional water insecurity, potentially leading to operational delays and even shutdowns. These challenges underscore the need for the EU to go beyond the extraction operation, but offer its engineering and environmental expertise and pursue a systemic approach to its partnership with Kazakhstan.

Uzbekistan

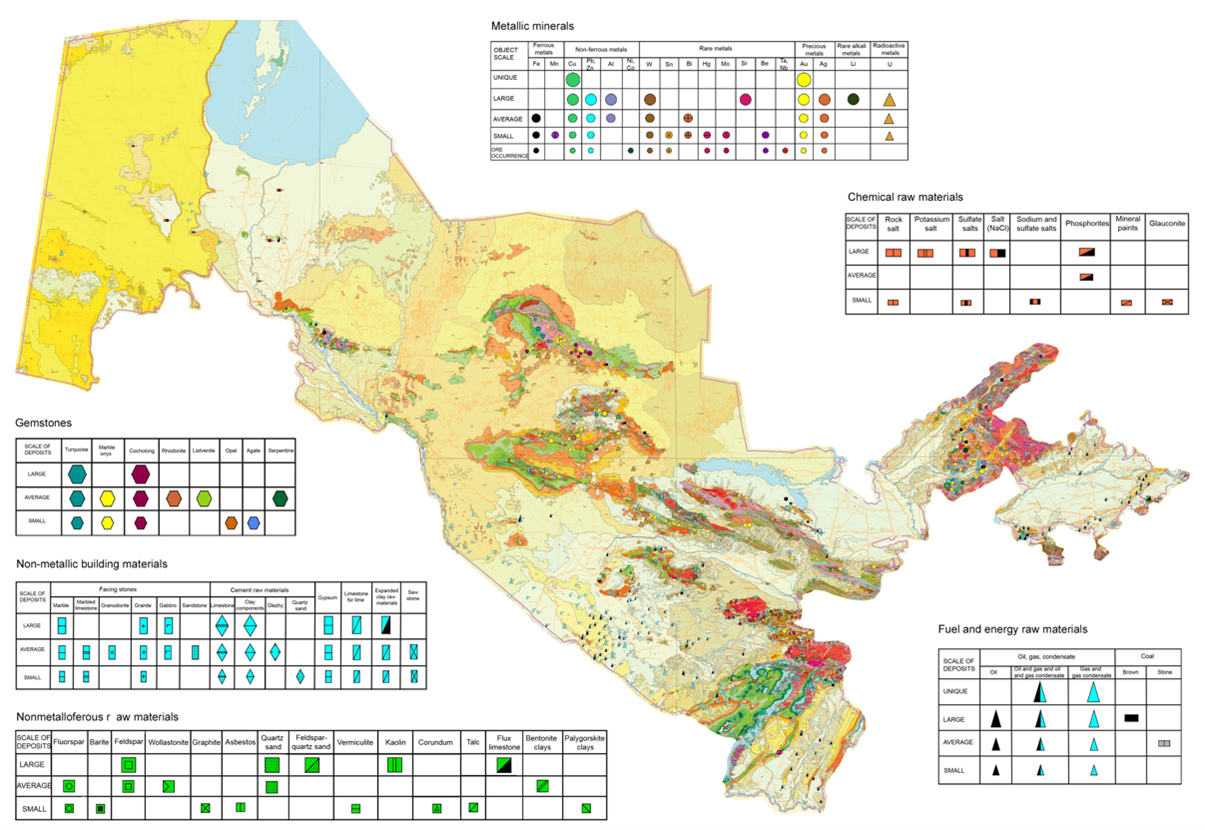

Figure 3: Uzbekistan Mineral Resources Map. Source: Geoportal of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is the fifth-largest uranium supplier worldwide, with rich reserves of silver, titanium, molybdenum, and gold. Moreover, Uzbekistan possesses significant reserves of at least 7 out of 32 CRMs listed in the 2020 EU CRMs List including lithium, gemanium, titanium, vanadium, tungsten and graphite.

With a reform-oriented government and a proven track record of economic liberalization, Uzbekistan emerges as a reliable and secure partner in Central Asia. Its substantial, if underexploited reserves of CRMs, developed under transparent investment frameworks and inspired by mutual agreements, will offer the EU a unique opportunity to diversify supply chains and reduce strategic dependencies. However, while the EU-Uzbekistan Partnership agreement laid the foundation for future collaboration, tangible progress beyond regular meetings has been modest.

Uzbekistan’s mining sector, despite recent reforms and a US$2.6 billion initiative to develop mineral resources, still faces limitations in infrastructure and technological capabilities, a commonplace in the region. Investors may need to bring their own expertise, knowledge, equipment, and massive influx of capital to maximize project success in the market still dominated by the state-owned enterprises.

Furthermore, although Uzbekistan has demonstrated a commitment to improving its regulatory environment and attracting foreign investment, the long-term reliability of agreements can be influenced by the broader political and legal context. Ongoing reforms are expected to further strengthen the investment climate, but for now, these factors require careful consideration as part of any major partnership in the CRMs sector. Recognizing and deepening the partnership with Uzbekistan will be essential for both regional cooperation and the EU’s long-term resource security – but evident improvements on investment climate on Uzbekistan’s side are condition for such a partnership to flourish.

With a reform-oriented government and a proven track record of economic liberalization, Uzbekistan emerges as a reliable and secure partner in Central Asia. Its substantial, if underexploited reserves of CRMs, developed under transparent investment frameworks and inspired by mutual agreements, will offer the EU a unique opportunity to diversify supply chains and reduce strategic dependencies. However, while the EU-Uzbekistan Partnership agreement laid the foundation for future collaboration, tangible progress beyond regular meetings has been modest.

Uzbekistan’s mining sector, despite recent reforms and a US$2.6 billion initiative to develop mineral resources, still faces limitations in infrastructure and technological capabilities, a commonplace in the region. Investors may need to bring their own expertise, knowledge, equipment, and massive influx of capital to maximize project success in the market still dominated by the state-owned enterprises.

Furthermore, although Uzbekistan has demonstrated a commitment to improving its regulatory environment and attracting foreign investment, the long-term reliability of agreements can be influenced by the broader political and legal context. Ongoing reforms are expected to further strengthen the investment climate, but for now, these factors require careful consideration as part of any major partnership in the CRMs sector. Recognizing and deepening the partnership with Uzbekistan will be essential for both regional cooperation and the EU’s long-term resource security – but evident improvements on investment climate on Uzbekistan’s side are condition for such a partnership to flourish.

Tajikistan

Figure 4: Tajikistan Mineral Resources Map. Source: Geoportal of Tajikistan

The EU has yet to conclude any specific bilateral memoranda or strategic agreements with Tajikistan. Tajikistan forms part of EU’s cooperation efforts within the region through the EU-Central Asia Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, the EU-Central Asia Strategy, and other regional agreements. Importantly, Tajikistan is the world’s second largest antimony producer accounting for 26% of global output and supplying 42% of all antimony imported into the EU. Additionally, Tajikistan possesses at least 12 out of the 32 CRMs in the EU list, including aluminum, boron, strontium, fluorspar and tungsten.

Despite its significant potential as a partner, the EU currently lacks tangible, formal agreements with Tajikistan in the mining and CRMs sectors. This absence draws in competition from Russia and China. China has already emerged as Tajikistan’s largest creditor and primary investor in joint mining ventures, while Russia remains one of Tajikistan’s most important trading partners.

Through its soft-power approach, the EU has a unique opportunity to become one of the first major investors in developing Tajikistan’s mining capabilities and extracting its abundant resources. By doing so, the EU can expand its network in Central Asia while upholding its high standards for institutionalized and formalized agreements. Such an approach would not only secure access to CRMs but also promote sustainable development and good governance in the region.

Tajikistan has taken concrete steps to attract EU investment. The government has established an investment framework that guarantees stability for mining projects and is actively pursuing value-added processing strategies. Tajikistan also benefits from and participates in the EU’s Global Gateway investment program, which supports infrastructure, energy, and digital connectivity projects. These efforts demonstrate Tajikistan’s readiness for partnership and its commitment to aligning with international standards.

In summary, the EU’s proactive engagement with Tajikistan, backed by formal agreements and investment, could unlock significant opportunities for both sides, while counterbalancing the influence of other major powers in the region.

Despite its significant potential as a partner, the EU currently lacks tangible, formal agreements with Tajikistan in the mining and CRMs sectors. This absence draws in competition from Russia and China. China has already emerged as Tajikistan’s largest creditor and primary investor in joint mining ventures, while Russia remains one of Tajikistan’s most important trading partners.

Through its soft-power approach, the EU has a unique opportunity to become one of the first major investors in developing Tajikistan’s mining capabilities and extracting its abundant resources. By doing so, the EU can expand its network in Central Asia while upholding its high standards for institutionalized and formalized agreements. Such an approach would not only secure access to CRMs but also promote sustainable development and good governance in the region.

Tajikistan has taken concrete steps to attract EU investment. The government has established an investment framework that guarantees stability for mining projects and is actively pursuing value-added processing strategies. Tajikistan also benefits from and participates in the EU’s Global Gateway investment program, which supports infrastructure, energy, and digital connectivity projects. These efforts demonstrate Tajikistan’s readiness for partnership and its commitment to aligning with international standards.

In summary, the EU’s proactive engagement with Tajikistan, backed by formal agreements and investment, could unlock significant opportunities for both sides, while counterbalancing the influence of other major powers in the region.

Conclusion: Charting the Road Ahead

As the EU charts its path toward a green and digital future, securing reliable access to CRMs has emerged as a defining challenge. Central Asia, home to some of the world’s most significant reserves of CRMs, stands as the pivotal partner for the EU’s ambitions to diversify its supply chains and reduce dependence on a limited number of global suppliers.

Kazakhstan remains the EU’s most established and reliable partner in the region. With the capacity to produce or process up to 21 of the EU’s 32 CRMs, Kazakhstan plays a central role in the EU’s CRMs strategy. The robust partnership between the two is cemented by a Memorandum of Understanding on Sustainable Raw Materials, the Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, and detailed implementation roadmaps. These agreements not only facilitate trade and investment but also promote research and innovation.

However, overreliance on Kazakhstan may prove risky in the long term and highlights the need for the EU to broaden its network of reliable partners across Central Asia. Uzbekistan, with its significant reserves of at least seven CRMs, presents a key opportunity for the EU. Uzbekistan’s progress in establishing transparent investment frameworks and participating in the EU’s partnership agreements demonstrates its readiness for deeper collaboration. Tajikistan, though less integrated into the EU’s CRMs strategy, holds vast untapped potential and has taken concrete steps to attract EU investment. The absence of formal, bilateral CRMs agreements with the EU leaves the country seeking cooperation opportunities elsewhere, underscoring the urgency for the EU to act decisively.

While often criticized for bureaucratism, EU’s approach of formalized agreements and targeted investment may not only secure long-term access to CRMs but provide solid foundations to foster regional stability and back up ambitious connectivity projects, including the Middle Corridor. The EU’s strategic imperative should be clear: diversify, deepen, and formalize partnerships across Central Asia. Proactive engagement, backed by investment, technical assistance, and expertise-sharing, will enable the EU to build resilient, sustainable supply chains – a key to mutual economic growth and development.

Kazakhstan remains the EU’s most established and reliable partner in the region. With the capacity to produce or process up to 21 of the EU’s 32 CRMs, Kazakhstan plays a central role in the EU’s CRMs strategy. The robust partnership between the two is cemented by a Memorandum of Understanding on Sustainable Raw Materials, the Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, and detailed implementation roadmaps. These agreements not only facilitate trade and investment but also promote research and innovation.

However, overreliance on Kazakhstan may prove risky in the long term and highlights the need for the EU to broaden its network of reliable partners across Central Asia. Uzbekistan, with its significant reserves of at least seven CRMs, presents a key opportunity for the EU. Uzbekistan’s progress in establishing transparent investment frameworks and participating in the EU’s partnership agreements demonstrates its readiness for deeper collaboration. Tajikistan, though less integrated into the EU’s CRMs strategy, holds vast untapped potential and has taken concrete steps to attract EU investment. The absence of formal, bilateral CRMs agreements with the EU leaves the country seeking cooperation opportunities elsewhere, underscoring the urgency for the EU to act decisively.

While often criticized for bureaucratism, EU’s approach of formalized agreements and targeted investment may not only secure long-term access to CRMs but provide solid foundations to foster regional stability and back up ambitious connectivity projects, including the Middle Corridor. The EU’s strategic imperative should be clear: diversify, deepen, and formalize partnerships across Central Asia. Proactive engagement, backed by investment, technical assistance, and expertise-sharing, will enable the EU to build resilient, sustainable supply chains – a key to mutual economic growth and development.