With its young and tech-savvy population, who use mobile as their primary means of communicating with the digital world, Central Asia is moving toward a digital payments economy that is expected to surpass USD 250 billion by 2026. The story of local fintech champions successfully challenging the established players - banks and card payments - has been replayed many times in China, India, Brazil and elsewhere. Yet, the road to fintech revolution in Central Asia is an illustration of how policy choices created, shaped and often enabled this tremendous growth - quite possibly to the surprise of its early architects nearly two decades ago.

The early years: Slow Start, Explosive Growth

When in 2004 Uzbekistan’s Central Bank launched its own card processing system - Republican Processing Center, later rebranded as Uzcard - few would have suspected its transformative potential for a country where the percentage of people with bank accounts ran in single-digits. However, the main reason behind the introduction of a state-owned card system at the time was not a visionary adoption of the emerging open banking approach, but the acute cash shortage. Twenty years later, Uzbekistan’s open banking protocols enabled a booming ecosystem of 44 payment organizations, 12 digital money systems, and two formerly state-owned card processing systems outcompeting Visa and Mastercard in the domestic market. The cash share in the economy fell to record lows under 20% in 2025.

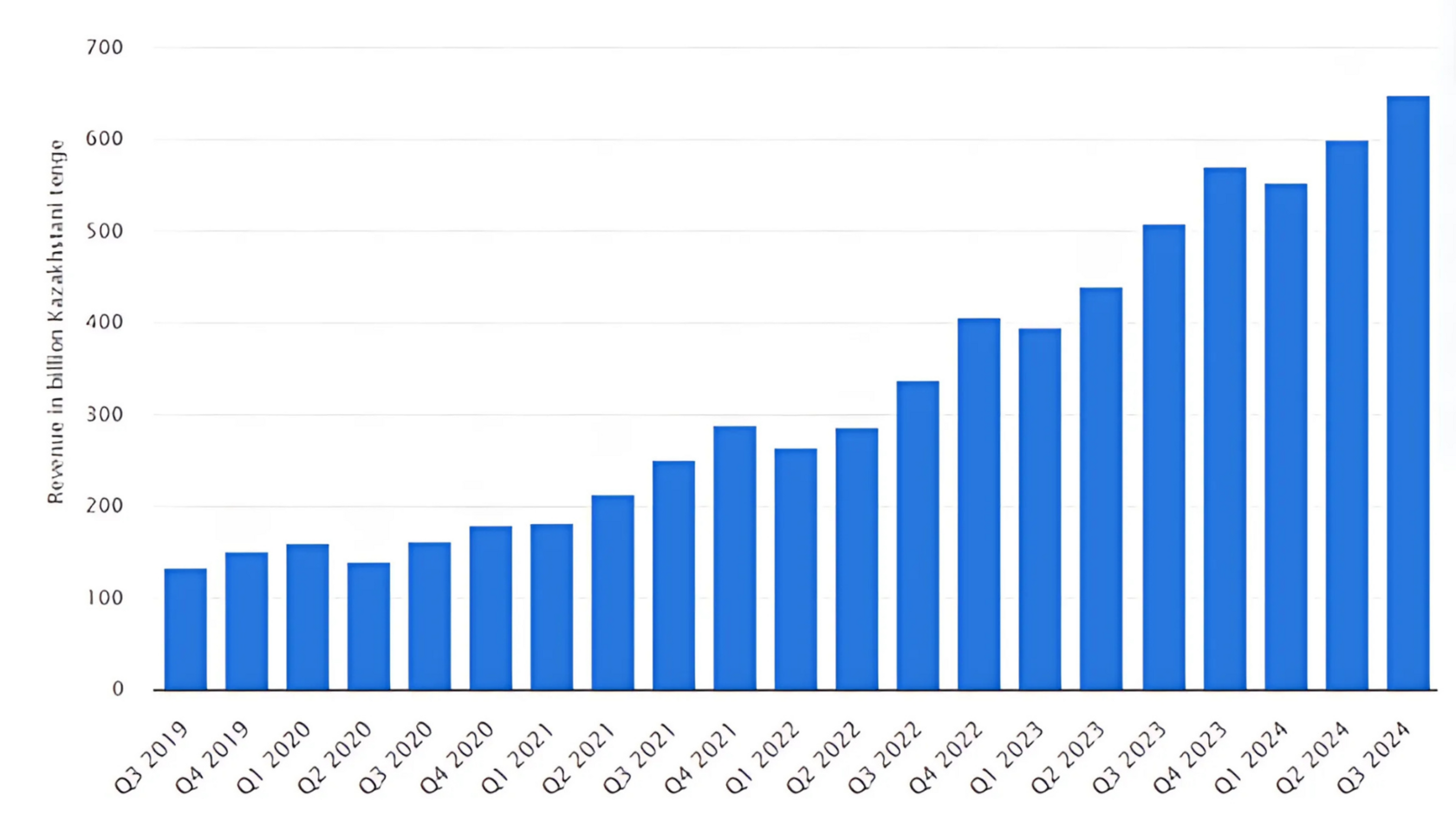

Around the same time, an aspiring entrepreneur in the neighbouring Kazakhstan purchased one of the small recently-privatized banks to provide loans to his retail chain customers and brought in partners from a venture capital firm seeking synergy. The partners shortened the bank’s name to a catchy Kaspi, dropped all businesses but consumer deposits, loans and cards, and in the next decade remade it into the e-commerce ecosystem centered around a sleek mobile app. Since the launch of its QR payment system Kaspi became the default mode of payment in the entire country - from stores to government services - and Central Asia’s first fintech unicorn, setting the regional blueprint for building integrated superapps and ecosystems.

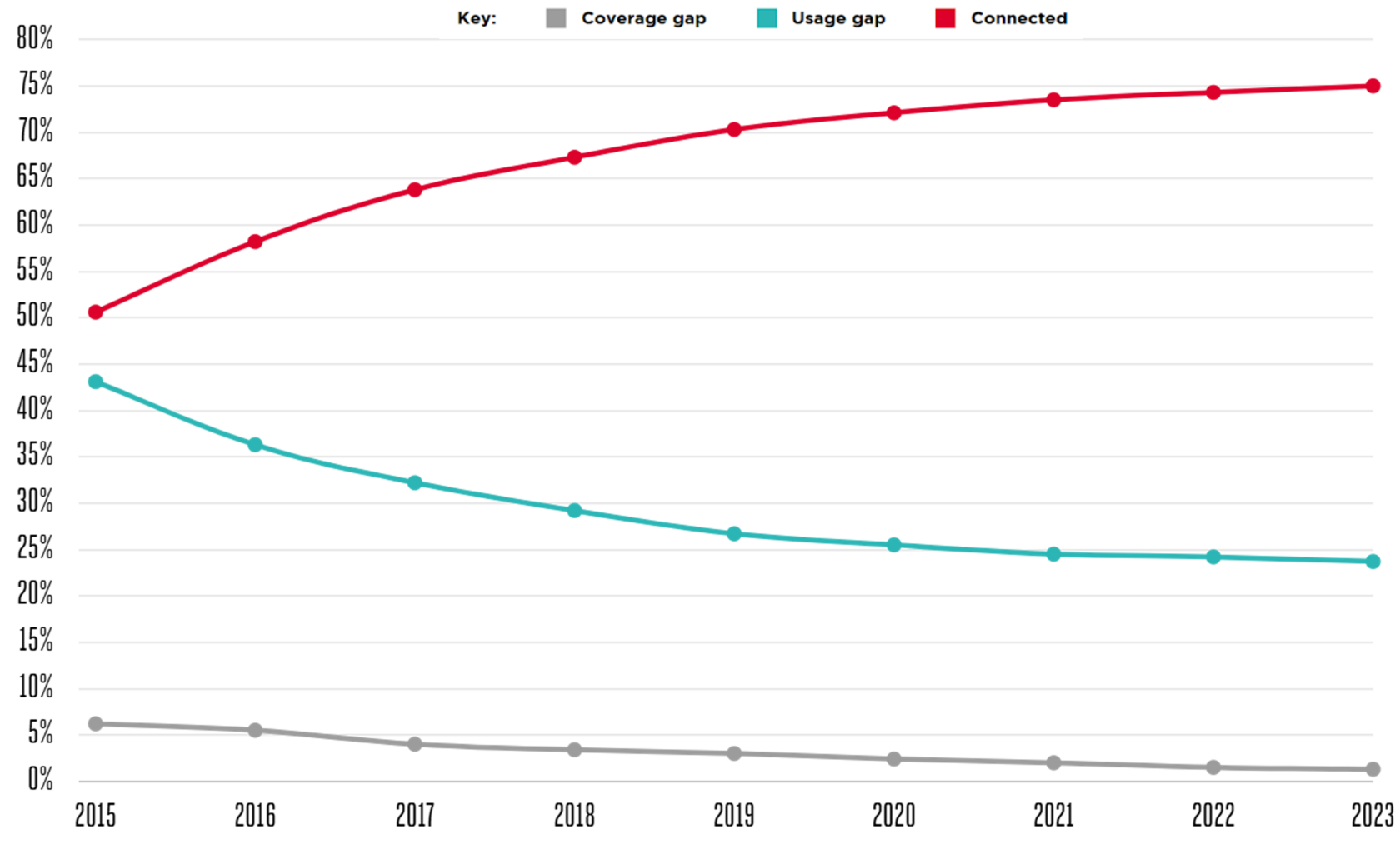

For all the differences between the two fintech success stories - a state-orchestrated move away from cash in Uzbekistan and a private enterprise doing just the same in Kazakhstan - there are notable similarities. First of all, these initiatives stemmed from the unique structural conditions of their markets at a specific period - the isolationist state-dominated economy in the former case, and the credit crunch of 2007-08 in the latter. Second, the fintech champions thrived on their ability to ride the waves of change, in particular the explosive growth of mobile internet usage and e-commerce in the last decade. Finally, while the well-being of local digital players was not the primary concern of their governments, the strict data localization requirements in both countries allowed local companies an advantage of having their data stored at home from the start.

Around the same time, an aspiring entrepreneur in the neighbouring Kazakhstan purchased one of the small recently-privatized banks to provide loans to his retail chain customers and brought in partners from a venture capital firm seeking synergy. The partners shortened the bank’s name to a catchy Kaspi, dropped all businesses but consumer deposits, loans and cards, and in the next decade remade it into the e-commerce ecosystem centered around a sleek mobile app. Since the launch of its QR payment system Kaspi became the default mode of payment in the entire country - from stores to government services - and Central Asia’s first fintech unicorn, setting the regional blueprint for building integrated superapps and ecosystems.

For all the differences between the two fintech success stories - a state-orchestrated move away from cash in Uzbekistan and a private enterprise doing just the same in Kazakhstan - there are notable similarities. First of all, these initiatives stemmed from the unique structural conditions of their markets at a specific period - the isolationist state-dominated economy in the former case, and the credit crunch of 2007-08 in the latter. Second, the fintech champions thrived on their ability to ride the waves of change, in particular the explosive growth of mobile internet usage and e-commerce in the last decade. Finally, while the well-being of local digital players was not the primary concern of their governments, the strict data localization requirements in both countries allowed local companies an advantage of having their data stored at home from the start.

Mobile Internet Connectivity, Europe and Central Asia, GSMA

In many ways, the evolution of fintech in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan resembled the digital payments trajectories in China and India respectively. Similar to Kazakhstan, the Chinese e-payment boom was driven by private sector players - like Alibaba and WeChat. The companies developed payment solutions within their own expansive ecosystems - both B2B and B2C - and gained massive traction with a massively underbanked population in a relatively unrestricted regulatory environment. India’s United Payment Interface (UPI) was designed by the country’s central bank - Reserve Bank of India - as a public utility to curb the cash dominated informal economy and allow financial inclusion of hundreds of millions of citizens through cheap smartphones and even feature phones. A similar combination of government priorities, cheap handhelds, and some 'working around' regulations gave rise to Uzbek fintech pioneers, like Click and Payme.

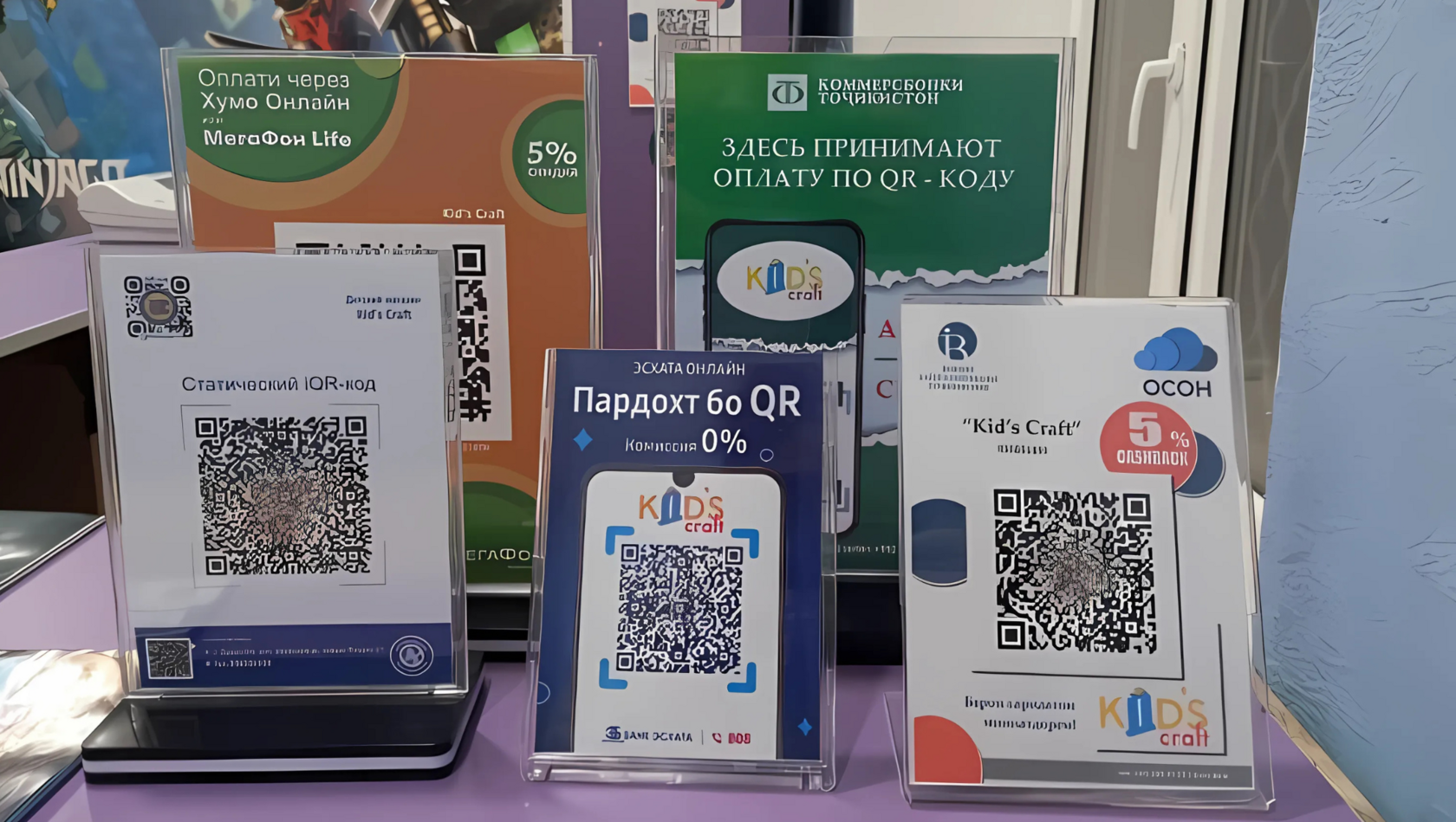

Other countries in the region are seemingly looking at the same playbook. Kyrgyzstan’s Central Bank launched its own card processing system Elcart in the same year as Uzbekistan - twenty years later both countries announced plans to integrate Elcart and Uzcard to allow cross-border transfers and acceptance. Tajikistan's Alif is driving QR code payments acceptance by offline merchants in cooperation with the local state-owned card transaction systems Korti Milli and global players like Visa and Mastercard. Even Georgia, a country where liberal financial regulation created two banking giants - TBC Group and Bank of Georgia - fully integrated into the global financial system now considers developing its own domestic payment system.

Other countries in the region are seemingly looking at the same playbook. Kyrgyzstan’s Central Bank launched its own card processing system Elcart in the same year as Uzbekistan - twenty years later both countries announced plans to integrate Elcart and Uzcard to allow cross-border transfers and acceptance. Tajikistan's Alif is driving QR code payments acceptance by offline merchants in cooperation with the local state-owned card transaction systems Korti Milli and global players like Visa and Mastercard. Even Georgia, a country where liberal financial regulation created two banking giants - TBC Group and Bank of Georgia - fully integrated into the global financial system now considers developing its own domestic payment system.

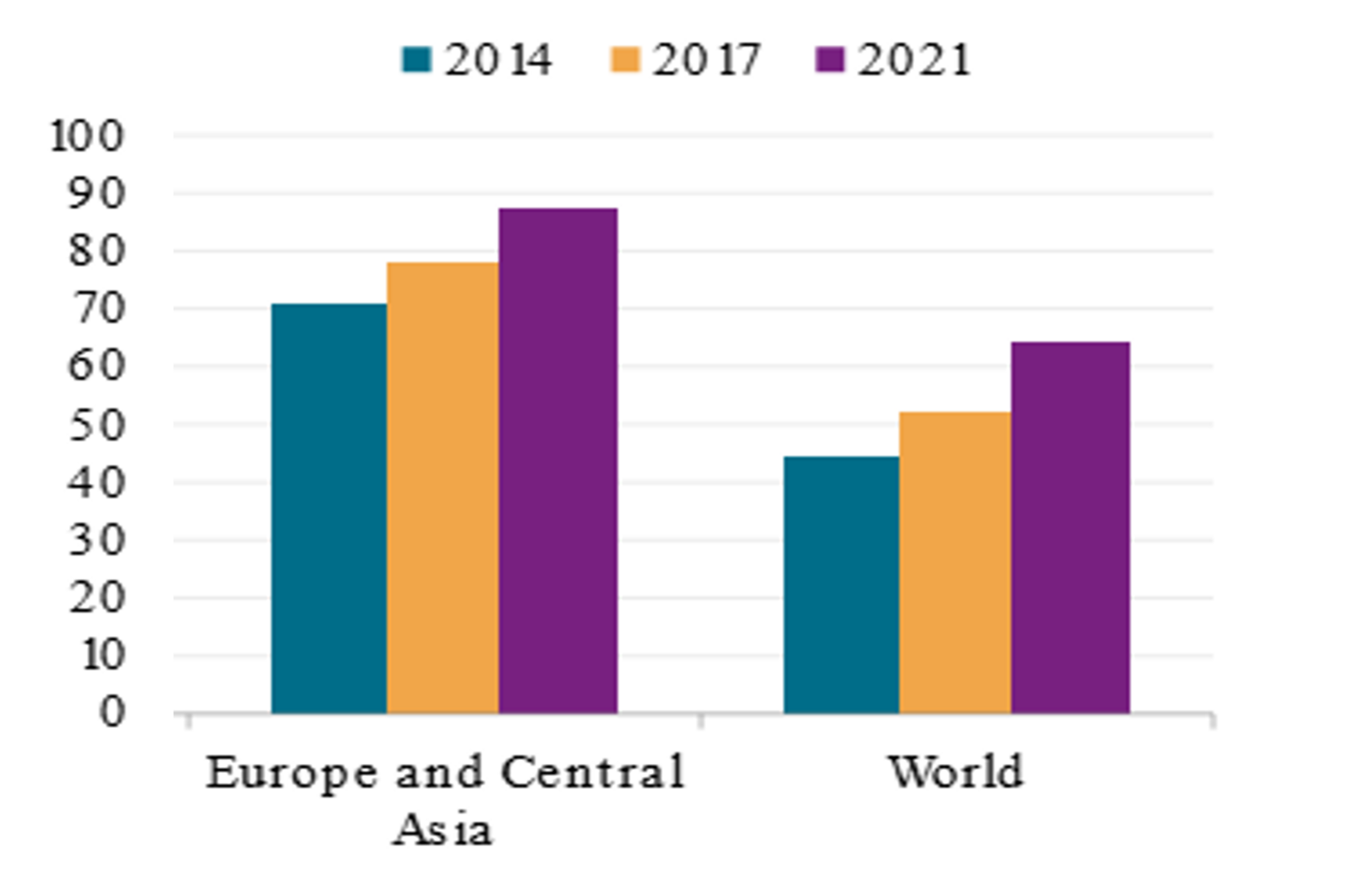

Made of Received Digital Payments, Europe and Central Asia, Standards & Poor

Today: Challenges Appear, Rules Set In

The friction between fintech players, regulators, banks, and users continues to shape the industry’s complex landscape. The rapid fintech adoption put the emerging tech champions on the collision course with the regulatory frameworks built for the earlier era.

One critical aspect where regulators and consumers interests align and often go against the fintech business models is the interoperability between the various digital ecosystems. Kaspi’s ‘walled garden’ approach in Kazakhstan allowed it to become the dominant player, putting aside not just cash, but all other payment means and players. Facing a similar situation with its two most popular payment systems - Alipay and WeChat - being incompatible with each other and with the country’s own UnionPay cards, in 2019 Chinese Central Bank initiated a regulatory push to achieve interoperability. Kazakhstan in turn chose to develop a unified QR code payment system back in 2022, and the system currently tested by about half of the country’s banks is expected to become fully operational by the end of 2025. In Uzbekistan, ensuring interoperability of the two local card payments systems Uzcard and Humo in ATM and POS terminals took almost three years - and it is unclear how long the newly announced QR code standard will take in development and implementation between several leading operators.

One critical aspect where regulators and consumers interests align and often go against the fintech business models is the interoperability between the various digital ecosystems. Kaspi’s ‘walled garden’ approach in Kazakhstan allowed it to become the dominant player, putting aside not just cash, but all other payment means and players. Facing a similar situation with its two most popular payment systems - Alipay and WeChat - being incompatible with each other and with the country’s own UnionPay cards, in 2019 Chinese Central Bank initiated a regulatory push to achieve interoperability. Kazakhstan in turn chose to develop a unified QR code payment system back in 2022, and the system currently tested by about half of the country’s banks is expected to become fully operational by the end of 2025. In Uzbekistan, ensuring interoperability of the two local card payments systems Uzcard and Humo in ATM and POS terminals took almost three years - and it is unclear how long the newly announced QR code standard will take in development and implementation between several leading operators.

Kaspi revenue in KZT, 2019-2024, Statista

Rapid adoption of digital loans enabled by fintech is another area where massive opportunities for business growth come along with risks to financial stability. The ease of issuing and taking loans within fintech ecosystems unlocked pent up consumer demand - especially in Uzbekistan. Shariah-compliant digital BNPL solutions, such as Uzum Nasiya and Alif Nasiya, that allow customers without any formal credit score to purchase various goods online and at the point of sale are now one of the fastest growing categories, projected to account for over 20% of all e-commerce sales by 2027. However, the growing consumer debt along with the growth of non-performing loans led the Central Bank to take significant measures to cool down the demand for consumer loans in the last two years. As the supercharged growth of consumer lending will inevitably flatten, the fintech ecosystems will have to find their next ‘killer feature’ and the government will have to find a delicate balance between the indebtedness and consumption-driven economic growth.

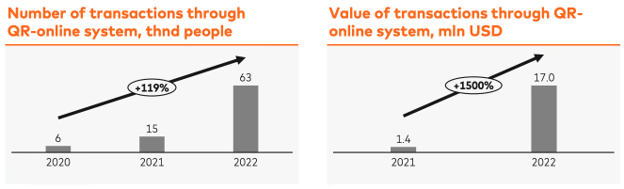

Transactions through QR-online system, Uzbekistan, Mastercard

In fact, the central banks have already stepped in to set the boundaries for non-banks fintechs in the areas it consider the most sensitive, such as AML and sanctions compliance, currency operations. For instance, in 2023 Uzbek regulators sent the business of one of the country’s leading digital payments provider Oson into a tailspin by reiterating an existing clause preventing non-banking organizations from opening foreign accounts and servicing cross-border transactions. The subsequent regulation on capital adequacy and ownership structure made requirements for digital payments operators similar to regulations imposed on the Uzbek banks, and the resulting cleanup reduced the number of payment organizations in the market by a third in just two years. This year the focus of Kazakh and Uzbek regulators has shifted attention to transactions related to gambling and betting, cryptocurrencies, and AML/CTF requirements, ultimately aiming to achieve the same level of compliance and transparency of transactions by fintech players as one would expect from banks.

Cross-border payments is another illustration of the institutional limitations of Central Asia’s fintech players. While the cross-border trade and people movement demand interoperable real-time payments solutions (RTPs), the region remains fragmented in regulatory alignment, infrastructure standards, and currency convertibility, despite regional integration progress in many other areas. From this point of view, fintech solutions are already playing a critical role in enabling the flow of remittances from migrant workers in neighbouring countries, with Kaspi pioneering bank transfers to local card systems in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. However, the fintech potential of becoming driver of intraregional trade and tourism - the priority areas of Central Asia’s economic reintegration - remains underutilized.

Travelling with wads of cash may well be a thing of the past, but if holders of Mastercard and Visa cards do not have to worry about payment acceptance on the other side of the border, a far greater number of users of domestic payment systems are locked out of routine transactions anywhere else but home. To cater to the needs of Kazakh tourists Kaspi partnered with Alipay to unlock QR code payments first in China and then in 48 other popular leisure destinations - and yet remains unavailable in neighbouring Uzbekistan, visited by over a million of Kazakh tourists in 2024. In turn, this spring the Uzbek authorities announced plans to achieve integration of both WeChat and Alipay QR codes with the domestic payment systems.

Cross-border payments is another illustration of the institutional limitations of Central Asia’s fintech players. While the cross-border trade and people movement demand interoperable real-time payments solutions (RTPs), the region remains fragmented in regulatory alignment, infrastructure standards, and currency convertibility, despite regional integration progress in many other areas. From this point of view, fintech solutions are already playing a critical role in enabling the flow of remittances from migrant workers in neighbouring countries, with Kaspi pioneering bank transfers to local card systems in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. However, the fintech potential of becoming driver of intraregional trade and tourism - the priority areas of Central Asia’s economic reintegration - remains underutilized.

Travelling with wads of cash may well be a thing of the past, but if holders of Mastercard and Visa cards do not have to worry about payment acceptance on the other side of the border, a far greater number of users of domestic payment systems are locked out of routine transactions anywhere else but home. To cater to the needs of Kazakh tourists Kaspi partnered with Alipay to unlock QR code payments first in China and then in 48 other popular leisure destinations - and yet remains unavailable in neighbouring Uzbekistan, visited by over a million of Kazakh tourists in 2024. In turn, this spring the Uzbek authorities announced plans to achieve integration of both WeChat and Alipay QR codes with the domestic payment systems.

Beyond the limits, above the borders

With the countries’ vision of cashless economies aligned with the interests of the emerging fintech players made the relatively small region, lacking scale of India and China, or sophisticated tech industries of Southeast Asia and Russia, the hotspot of experimentation in fintech tools and models. By focusing on local realities, Central Asian fintech players have managed to bypass their own limits and build a dynamic, competitive and ever-evolving mobile-first ecosystem.

Central Asia’s only two tech unicorns - the integrated fintech/e-commerce ecosystems of Kazakhstan’ Kaspi and Uzbekistan’s Uzum - are themselves the proof of fintech’s transformative potential. Their success brought venture funds, institutional vendors and aspiring entrepreneurs to the region, driving innovations on the one hand and their adoption on the other. Along the way, the radical turn towards fintech and digital banking made by TBC Uzbekistan, which acquired the local payment system Payme, made conservative domestic banks follow the example and turned them into digital sandboxes.

The opportunities continue to be vast, even though the challenges for the existing models are starting to appear on the horizon. The local players that have relied on addressing the needs of their domestic markets may find their scale insufficient to sustain growth. Market saturation in Kazakhstan is already within sight and in a few years time the limits of purchasing power in Uzbekistan and the region’s smaller economies will appear to the local players. The expansion potential within the region will be curtailed by fierce competition from both local and foreign players, including the traditional and digital-native banks, and even implicit protectionist measures.

There is however little doubt that agile fintech companies who learned to navigate the complex regualtory, technological, and societal aspects of Central Asia will continue to adapt. Some - like Kaspi - will use their market position in Central Asia as the launchpad for international expansion, merging e-commerce and banking enterprises elsewhere. Others, like Paynet - the Uzbek operator of the once ubiquitous payment kiosks and now the owner of the country's second largest card payment processing system - will double-down on domestic markets, expanding the breadth and depth of product offering. In any case, the curious case of Central Asia’s fintech industry boom will continue to be worth exploring.

Cover photo: Asia-Plus

Central Asia’s only two tech unicorns - the integrated fintech/e-commerce ecosystems of Kazakhstan’ Kaspi and Uzbekistan’s Uzum - are themselves the proof of fintech’s transformative potential. Their success brought venture funds, institutional vendors and aspiring entrepreneurs to the region, driving innovations on the one hand and their adoption on the other. Along the way, the radical turn towards fintech and digital banking made by TBC Uzbekistan, which acquired the local payment system Payme, made conservative domestic banks follow the example and turned them into digital sandboxes.

The opportunities continue to be vast, even though the challenges for the existing models are starting to appear on the horizon. The local players that have relied on addressing the needs of their domestic markets may find their scale insufficient to sustain growth. Market saturation in Kazakhstan is already within sight and in a few years time the limits of purchasing power in Uzbekistan and the region’s smaller economies will appear to the local players. The expansion potential within the region will be curtailed by fierce competition from both local and foreign players, including the traditional and digital-native banks, and even implicit protectionist measures.

There is however little doubt that agile fintech companies who learned to navigate the complex regualtory, technological, and societal aspects of Central Asia will continue to adapt. Some - like Kaspi - will use their market position in Central Asia as the launchpad for international expansion, merging e-commerce and banking enterprises elsewhere. Others, like Paynet - the Uzbek operator of the once ubiquitous payment kiosks and now the owner of the country's second largest card payment processing system - will double-down on domestic markets, expanding the breadth and depth of product offering. In any case, the curious case of Central Asia’s fintech industry boom will continue to be worth exploring.

Cover photo: Asia-Plus